Can Thunderstorms Spoil Milk?

The answer eluded scientists for centuries.

In 1858, John D. Caton, an Illinois Supreme Court Justice and amateur scientist, wrote a letter to Scientific American magazine. Published under the eye-catching title “Lightning and Milk,” Caton’s letter detailed an experiment he had performed in an attempt to explain what was then a familiar phenomenon. “It may not be generally understood by scientific men,” Caton began, “but it is well known to dairy men and housewives that a violent thunderstorm turns sweet into sour milk.”

In today’s world, it’s hard to imagine milk being directly affected by the weather unless one’s refrigerator breaks down. But it was once widely believed in both Europe and North America that thunderstorms could cause fresh milk to curdle, especially in summer. “At the time when it thunders, Beer, Milk, etc. turn sower [sour] in the Cellars,” Flemish alchemist Franciscus Mercurius van Helmont wrote in 1685. “The Thunder doth everywhere introduce corruption and putrefaction.”

That it happened was accepted, but why remained a puzzle throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Many theories placed the blame on the electricity created by a thunderstorm. In 1800, Noah Webster (of dictionary fame) hypothesized that lightning curdles milk by lowering the barometric pressure of the atmosphere. In 1857, just before Caton’s “Lightning and Milk” letter, writer Robert Evans Peterson suggested that lightning produces “a poison called nitric acid” that mixes into milk and curdles it. Others suggested the ozone gas released by reactions between lightning and the atmosphere could be affecting the milk.

Like many before him, Caton believed that the storm’s electricity was the cause of the mysterious curdling. To test this, he ran an electric current through bowls of milk using metal wires. Despite multiple trials with different types of wire, the electrified dairy failed to curdle. “I therefore concluded that electricity has no direct agency in turning sweet into sour milk during a thunderstorm,” Caton wrote. Later researchers came to similar conclusions, with some even finding that far from spoiling milk, a small amount of electricity helped preserve it. The power of storms over dairy remained an enigma.

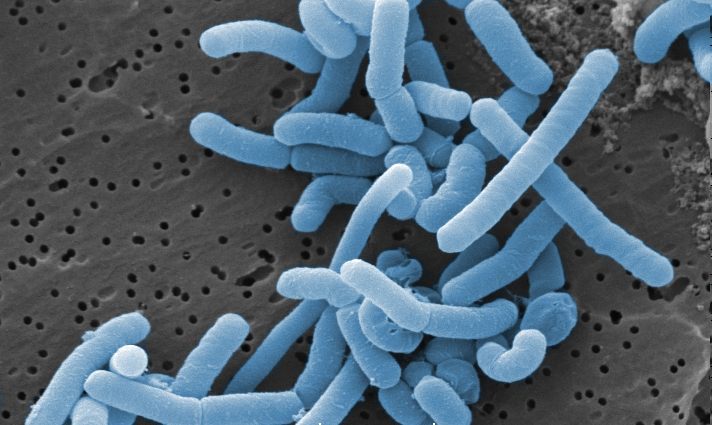

By the late 19th century, growing knowledge of microbiology and hygiene led to a departure from these earlier theories, as well as major changes in the way milk was consumed. Scientists learned that milk curdles not because of atmospheric fumes or electric shocks, but because of bacteria. When microbes consume the milk’s natural sugars (lactose), they produce lactic acid as a waste product. This coagulates the milk’s proteins, creating lumps and making the milk taste sour. Warm, damp conditions help bacteria grow, while technologies like pasteurization and refrigeration make things too hot or cold for bacteria to thrive.

The first scientist to posit bacteria as the real connection between storms and spoiled milk may have been Aaron L. Treadwell, whose own experiment was described in Science in 1891. If some chemical or charge in a stormy sky were the cause of sour milk, Treadwell reasoned that it should affect sterilized and unsterilized milk equally. However, he found that after exposure to simulated storm conditions, pasteurized milk curdled less than raw milk fresh from the cow. “It seems to me most likely,” Treadwell wrote, “that whatever rapid souring occurs is due to an unusually rapid growth of bacteria, caused by especially favorable conditions of the atmosphere.”

By 1927, Edward Holyoke Farrington was presenting this explanation as a matter of fact in A Guide to Quality in Dairy Products, published by the University of Wisconsin. “A thick, sultry atmosphere usually precedes thunder showers and provides favorable conditions for the growth of milk-souring bacteria,” Farrington wrote. He also noted another significant factor: “the condition of the milk cans.” If milk is stored in unsanitized vessels that already harbor bacterial cultures, it will curdle even faster when exposed to the warm, wet air bacteria love. “No effect from thunder and lightning on milk and cream will be noticed,” Farrington assured readers, so long as the milk was chilled, and “if the cows are clean, the milk cans are clean, and all the utensils carefully sterilized.”

Treadwell’s and Farrington’s assertions still hold up today, according to a 2020 study published in the German journal Chemistry in Our Time. However, not all scientists were immediately convinced. In 1937, The Telegraph ran an article entitled “Thunderstorm-Curdled Milk Puzzle Still Baffles Science,” featuring yet another theory, that electrically-charged air molecules accelerate decay (while also noting that there was no evidence to support this). But as pasteurized, refrigerated milk became the commercial standard, fast-spoiling, bacteria-laden raw milk became a thing of the past for many. This also meant that many people forgot about the supposed connection between storms and milk, and scientists largely stopped trying to explain it.

The belief that thunder curdles milk still persists in some rural areas where raw milk is consumed, especially among older generations. (A recent discussion of the topic on Reddit was entitled “What was my grandma talking about?”) Before people had access to refrigeration or knew about microbes, the proliferation of bacteria in unsterilized milk pails during a humid summer storm seemed mystical. But it wasn’t necessarily cause for alarm. Some sources suggested that if a storm spoiled your milk, you could make the best of things by eating it like yogurt, with a sprinkling of sugar. However, this unusual delicacy might not be worth the risk of consuming unrefrigerated raw milk, especially once you know that it was soured by bacteria, and not by lightning.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook